When Singapore’s founding prime minister Lee Kuan Yew died this March, questions rang out across the globe. Was this the end of an era? More specifically, as an international student from neighboring Malaysia watching from abroad, I wondered: Would it be the end of the only style of governance Singapore has known?

Critics were hopeful. For 56 years, Lee’s founding party, the People’s Action Party (PAP), has enjoyed national autonomy, and his son, Lee Hsien Loong, is Singapore’s prime minister today. “There’s a genuine, palpable desire for people wanting political plurality,” PN Baljii, former deputy editor of The Straits Times, argued. “That’s been like a genie kept in a bottle, and now the genie is completely out.”

From London, Tan Wah Piow, an exiled former political prisoner and lawyer, declared that Lee’s death would “set the people free.”

But those clamoring for greater civil liberty needn’t have gotten their hopes up, and it’s chiefly because of this: freedom would not be reborn in Singapore, as it was not considered to be dead in the first place.

It begins with the fact that the ideals of freedom recognized in the West conventionally have not ever and will likely never conflate with those of Singaporeans.

Lee’s greatest leadership success is touted as making the advancement for political order by linking it with prosperity.

To this day, Singaporeans cannot legally buy chewing gum or hold protests anywhere outside of specifically designated areas, but they enjoy one of the world’s highest per capita incomes and a standard of living superior to almost anywhere else – a far more important priority if you ask many residents, particularly when you factor in that the majority of the world is still considered to be “low-income,” according to a new Pew study.

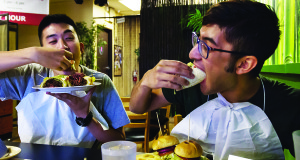

At a memorial for the former prime minister, a Singaporean interviewed by The New York Times probably pronounced it best: “As long as you are economically well off, with housing and food, who cares about the politics?” he said. “I would much rather live in a country like this than a place where you have every freedom in the world but you are hungry.”

This tendency to split up political freedom and economic mobility was promoted, but not constructed by Lee. For generations, the keep-your-head down mentality has reverberated throughout Asia, particularly in countries fresh out from colonial rule or prominent authoritarian agendas. A historical study of student protests in Asia concluded that activism suffered from a theme of inconstancy, swaying from having “highly charged ideas” to “lapsing into irrelevance.”

As pro-democracy demonstrations unfolded in Hong Kong, another special administrative region often compared to Singapore for its neoliberal style of governance, one student from the city declared her belief that growing up, “democracy was not for everyone.”

“I would scoff in my Gov. 20 section at idealistic students who wholeheartedly embraced democratization,” she wrote in a Harvard Crimson op-ed. “I always appreciated the efficiency and perks of a large civil service and government unencumbered by all the fuss associated with the election cycle.”

Even with the loss of a figure as intimidating as Lee, a shift in Singapore’s political landscape is unlikely – a recent example being Amos Yee, the 16-year-old jailed in July for 53 days after criticizing the government and Christians in a video. While the court eventually submitted to mounting international pressure, this didn’t stop some Singaporeans from publicizing the “shame” they saw in him.

From a regional perspective, it’s not entirely difficult to understand the logic of Singaporean satisfaction. Elsewhere in Southeast Asia, the region is continuing to undergo arguably far greater failures in what the Council on Foreign Relations has called “a regression from democracy,” with Malaysia’s ongoing corruption probe, Thailand’s military coup and persistent conflict along the Burmese-Chinese border.

In Mainland China, a country at least respected for an indisputable economic ascent, people continue to face everyday restrictions like the ban on Facebook, while nations like the Philippines, championed as “Asia’s oldest democracy,” still leave much to be desired by way of economic development.

To many Singaporeans, it seems hard to have it both ways, and it’s probable that in the next election, they’ll be sticking with what they know.

VOICES Publishing from the AAJA National Convention

VOICES Publishing from the AAJA National Convention