Growing up in the central province of Hubei, Xiao Da Wei never once considered staying in China for university.

Xiao, a 23-year-old civil engineering major, is one of the more than 225,000 Chinese students pursuing higher education in America, according to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Many of those students were right on his campus, the University of Southern California.

China, with one-third of all international students, has by far has the largest group of students abroad, according to the Institute of International Education (IIE).

Most Chinese students studying abroad choose American universities. Though a college degree here costs far more than those offered in other countries, the U.S. remains the leader in hosting international students from around the world, with almost double the number studying in the U.K., the second-largest host country, according to the IIE.

The numbers are rising, but why so many students choose to go overseas for their education isn’t always immediately clear. In the 2013-2014 academic year, more than 886,000 foreign students were in the U.S., marking a record high in almost a decade of continued growth, noted an IIE report.

Where do international students like to go?

All four institutions hosted more than 10,000 international students in the 2013/2014 school year

| Rank | School |

|---|---|

| 1 | New York University |

| 2 | University of Southern California |

| 3 | University of Illinois—Urbana-Champaign |

| 4 | Columbia University |

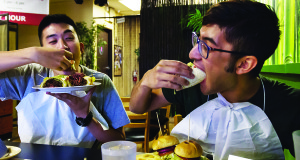

Xiao says he also wanted a more varied experience than one he believed was possible in his home country, from an emphasis on the liberal arts to more extracurricular opportunities to the prospect of making new friends. “I wanted to learn to be more social and make more interpersonal connections with a diverse group of people,” he said. “But in China, you always stay with the same people.”

Students like Xiao have parents who believe an education abroad will bring greater returns than one back home.

The costs of preparing for and completing an overseas degree can reach anywhere between RMB 1 million and 2 million ($165,000-$330,000), according to The Financial Times.

But while a federal requirement demands that international students prove their ability to pay at least the first year of school up front, money isn’t the only barrier. Going abroad is a substantially more cumbersome process, with the tests and classes in a second language, the difficulty of being away from family and a profound burden of culture shock.

So why do Chinese students keep doing it?

The reasons vary, said Xiao, a fifth-year student who completed his undergraduate studies at USC in May and is staying on for a master’s degree in construction management.

To begin with, the Chinese university system is structured in such a way that getting into a top school in the U.S. is actually far more likely than attending one locally, he said.

Being from Hubei’s provincial capital of Wuhan, for instance, Xiao didn’t even consider applying to Beijing’s Tsinghua University and Peking University — also known as China’s version of Oxbridge — because he thought he couldn’t get in.

“I can get into like, the top five, but not Tsinghua Beida,” he said, referring to the schools’ Chinese names.

Like millions of other students, Xiao was automatically subject to a higher “score line” than the local residents of Beijing, a setup that The Atlantic reports “reinforces the country’s inequalities.”

Dr. Natasha Warikoo, an associate professor at Harvard University who studies race, ethnicity and education, said she has encountered a similar narrative among students from both China and India.

“People want to go a top college, they don’t get into those top places. The joke is that, well, Harvard is their second choice, right? And then they go to a U.S. university,” she said.

It hasn’t been easy for Xiao to get to where he is now. Disappointed by his SAT scores in high school, he decided to take a gap year to study English and work on writing and critical reading.

In comparison to most applicants who take the test “once or twice,” according to The College Board, Xiao traveled to Hong Kong to sit the exam a total of five times.

“I got under 2000 for SAT my senior year in high school,” he said. “I knew I wouldn’t get into any good schools with that score.”

It wasn’t until he managed to boost his score to 2100 — the highest score is 2400 — that Xiao sent out his applications. He selected only U.S. colleges, and “pretty much the top 20,” he said.

As offers streamed in from the University of Michigan, Universities of California Los Angeles and Berkeley, Rice University and USC, Xiao’s father advised him to go private, citing the smaller class sizes and associated prestige.

“The branding means it’s better. USC is posh, and favorite in China,” Xiao said.

Xiao acknowledges that he’s fortunate compared to many Asian students. Despite going to a top high school in China, he said only five in his class of 60 were able to afford an American college education.

“It’s seen as a privilege, definitely, yes of course. I feel like in China, all the people who have money want their kids to go to U.S.,” he said. “Even many professors’ children go.”

There have been challenges, though.

Despite being home to one of the country’s biggest international student populations, Xiao had to deal with cultural discrimination. His American roommate freshman year made fun of his accent and complained about the smell of his instant ramen, heaping tension to the point that the roommate eventually “asked to reassign,” he said.

And even after four years of living in the U.S., he’s been told in job interviews that his English must improve to be able to liaise with clients.

Xiao is now joining scores of other foreign grads vying for an American job — his next challenge.

His father’s advertising business provides a rare sense of security, though.

“I don’t have to worry about finding a job or anything,” he said. “I just want to know what it feels like to work in another country.”

VOICES Publishing from the AAJA National Convention

VOICES Publishing from the AAJA National Convention