Despite tensions over recent police killings of black people, police departments across the U.S. have been slow to equip officers with a tool civil rights activists say can help avert future tragedies: body-worn cameras.

“It’s happening, we always wish it would happen more quickly,” Tod Story of the Las Vegas chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union said of adoption of body cameras.

He says Las Vegas police statistics prove the devices’ effectiveness.

Story says there’s been a significant drop in complaints against officers, and also a drop from 12 fatal officer-involved shootings in 2011 to only two incidents so far in 2016.

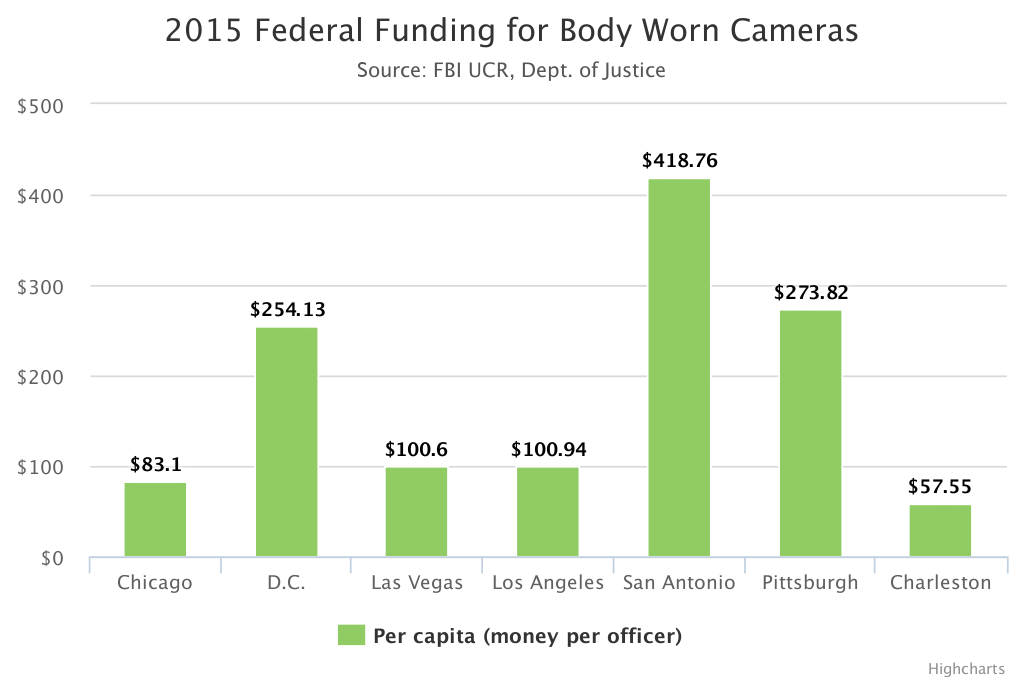

Darrell Stephens, executive director of the Major Cities Chiefs Association, said the U.S. Department of Justice has a grant program to help local departments adopt body camera programs, but the funding isn’t enough to meet demand, so body camera programs are being slowly phased in.

The Department of Justice awarded over $23 million for body cameras to 73 agencies in September, including departments from Los Angeles to Detroit, smaller sheriff’s offices and a Texas school district.

“There’s still some people that don’t believe what you gain from it is worth the costs,” Stephens said. “But with controversies over the last couple of years, there’s a greater sense of urgency.”

Las Vegas launched a body camera pilot program in 2013, and after developing policy from the test run, Metro had one of the first established body camera programs by September 2015.

The changes came after a 2011 Las Vegas Review-Journal investigation that preceded a Department of Justice inquiry which subsequently identified 73 deficiencies in the Vegas police department.

Story said most of the problems involve officers’ conduct with citizens. Better officer training has helped as have body cameras.

“There’s a different sense here in the community. There’s not as much of an ‘us vs. them’ mentality,” he says. “They now view the community as a partner rather than a threat.”

Las Vegas Police spokesman Michael Rodriguez said the body camera program has brought challenges such as adding a new technology into an already-trained officer’s routine.

“Certain things are ingrained in cops’ training since day one,” he said. “When you add something new like the camera, that’s just one more thing that the officer has to do.”

Rodriguez said another struggle for the department is finding funds for the initial investment of purchasing cameras while also paying continuously for storage capacity for the footage.

While the department has more than 1,000 cameras, Rodriguez said there’s still a deficit of at least 200 body cameras needed to fully equip the department.

Despite costs, Stephens predicts body cameras will spread soon enough as people see more examples of programs that work.

“Within five years, just about every large police department’s officers who are assigned to patrol areas will be wearing body cameras,” he said. “But maybe as we go forward, the cameras won’t be the panacea some people believe they’ll be.”

VOICES Publishing from the AAJA National Convention

VOICES Publishing from the AAJA National Convention