Eight years ago, the nation’s minority journalist groups met together in one convention — UNITY — and welcomed a presidential candidate that accepted an invitation to speak: Barack Obama.

This election year, there was no UNITY convention. NABJ and NAHJ formed a joint convention in Washington and snagged Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton as a speaker.

So far, AAJA appears to be missing out on luring the two leading presidential candidates for its conference in Las Vegas. Bill Clinton will be dispatched for his wife, but Donald Trump’s campaign has yet to confirm a representative. Libertarian presidential nominee Gary Johnson has announced his participation, as has Green Party candidate Jill Stein.

The decisions come as a blow to AAJA, which has been planning for a high-profile presidential town hall meeting aimed at the Asian American community with APIAVote, a nonpartisan group that mobilizes Asian Americans to vote. And it underscores how the messy divorce of the nation’s minority journalism groups from UNITY has arguably left some of its former members weaker than before.

“The potential for strength is so much greater when you have a united house and this house was divided,” said Joe Grimm, a former recruiter for the Detroit Free Press who attended every UNITY convention. “It’s so powerful when Asian journalists speak up for black journalists, speak up for Hispanic journalists, (and) speak up for gay journalists.”

After NABJ left in 2011, UNITY: Journalists of Color invited NLGJA to join the coalition and changed its name to UNITY: Journalists for Diversity. In 2013, NAHJ — the second largest coalition group — left.

The dissolution of the original coalition caused pain and anger among some of those who were with UNITY at its start.

“It’s not mine,” said Will Sutton, a cofounder of UNITY and a former NABJ president. “My intention and desire was to have journalists of color.”

Sutton and fellow reporter Juan Gonzalez came up with the idea of UNITY: Journalists of Color in the 1980s when they were both covering city hall in Philadelphia. The two were competitors in journalism but friends. Through informal and formal meetings, the two bridged the gap between NABJ and NAHJ.

Several years later, UNITY held its first conference in 1994, with more than 6,000 attendees and four minority journalists associations represented: NABJ, NAHJ, AAJA and NAJA.

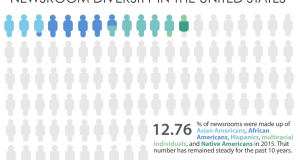

The sheer size of the group pushed media companies to recognize the importance of diversifying their staffs and increasing coverage of ethnic communities. It also made it easier for recruiters to meet talented non-white reporters in one central location.

UNITY continued to hold three more conferences, but the group fell apart after NABJ wanted a larger cut of the revenue. NABJ said it brought more than 50 percent of the attendees at the 2008 convention, yet received just 25 percent of the revenue based on the coalition’s model.

“We weren’t getting our fair share,” said Gregory Lee, NABJ treasurer at the time.

UNITY held one more convention with AAJA, NAJA, NAHJ and NLGJA in 2012, before shifting to smaller regional summits, said President Russell Contreras. A UNITY summit in Phoenix this year drew about 100 people.

The 2012 convention brought just $69,203 in net proceeds to AAJA, 61 percent less revenue than the 2008 convention when NABJ was part of the coalition.

But AAJA’s President Paul Cheung said his group hasn’t experienced a loss of influence with the changes in UNITY’s structure. Bringing presidential candidates to AAJA’s town hall for the AAPI community depended mainly on timing and location, Cheung said.

“I don’t think we lost out on anything,” he said.

There may be hope for a future UNITY convention. NAHJ President Mekahlo Medina said he would consider a joint conference if the revenue model was reworked to be more equitable. He said this year’s NAHJ and NABJ joint conference had a “proportional” revenue split, but didn’t provide details.

“If it’s going to cost you money, it doesn’t make sense,” Medina said.

Medina was just a high school student when he went to his first UNITY conference in 1994 and it had a powerful impact.

“It was the first time I felt such a massive representation of journalists of color doing what I wanted to do,” he said.

VOICES Publishing from the AAJA National Convention

VOICES Publishing from the AAJA National Convention